Speech Synthesis: Training and Inference

When I had finished cleaning the speech dataset, I was ready to train the speech model.

I had begun SOOTHER with the assumption that I would modify the MycroftAI system in order to serve my purposes. This assumption was based upon a limited survey of the field, and the observation that Macsen, which I planned to fork, was based on Mycroft Intent Parsers. MycroftAI is an open-source smart voice assistant, which is largely devised for smart speakers and other such devices, making it an awkward fit for my use-case. However, it is a modularly-designed system, and as such, you can pick and choose what components you use. Mycroft provides speech synthesis system via a library called Mimic2. Mimic2 is a fork of Keith Ito’s implementation of Google’s Tacotron paper, which described a system for end-to-end speech synthesis.[^1]

The Mimic2 fork, and Ito’s tacotron repo, contain a codebase that does the following:

- Analyse data (to observe standard deviation, etc.)

- Pre-process data (+ tips to build a custom pre-processor for your metadata csv & wav files)

- Train speech model

- Monitor training

- Synthesize voice with a simple server that queries the model at a given checkpoint

- And, provide docker files for GPU and CPU machines to run this entire process in docker

I decided to set up training in a multi-step process, namely:

- Run pre-processing on my local machine (2018 Thinkpad Carbon X1 w/16gb of RAM, Intel Core i7-8550U, Intel UHD Graphics 620) to ensure that data was properly formatted

- Run first ~1000 steps of training on my local machine to ensure that training could progress given my pre-processed data

Then,

- Port all of my data to an s3 bucket

- Get a really souped-up AWS instance

- Add the s3 bucket to said souped-up AWS instance as a docker volume

- Train

- Whisper & prosper

Issues arise in Inference

This process went smoothly up through the “train” step. I wrote a custom little pre-processer for my data, which was trivial based upon instructions and examples in the mimic2 repo. I successfully trained a speech model to 1000 steps on my local machine’s CPU, which took nearly a day. At 1000 steps, the model output audio that was definitely sounding like a whisper. See the early example in speech model demos.

I then deployed various AWS servers, rigged up my docker configurations, and started training with a p3 AWS instance. And the training worked! The voice was noticably improving at every checkpoint. I thought: this is easy! I let training run to 250,000 steps. Then, I tried running inference on the speech model. At training checkpoints, the model outputs audio samples derived from texts in its dataset. It already “knows” how they sound (this is called “guided” synthesis). In inference, you ask the model to speak something entirely new. And at 250,000 steps, when I asked my model to speak in inference, it catastrophically no worky, as we say in the business.

Issue 1: Lack of Alignment

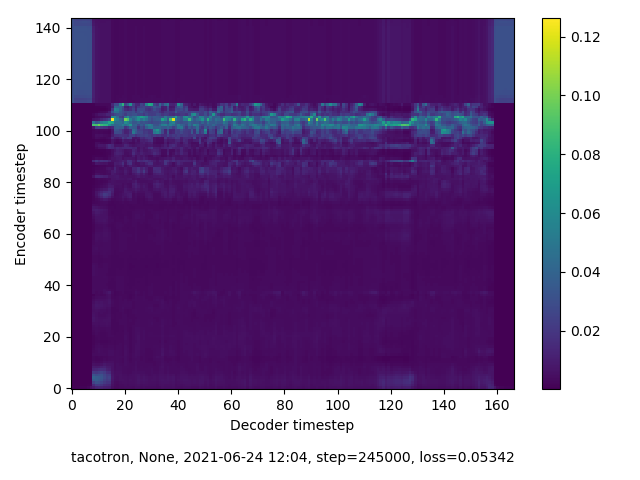

Look, reader, I’d never trained an AI before, and I have a personal flaw, which is that I hate to read instructions. I’m a real fuck-around-and-figure-it-out kind of person. So, it took me longer than it should have to realise that the spectrograms my model was outputting at checkpoints indicated that it was never going to reach alignment. They looked like this:

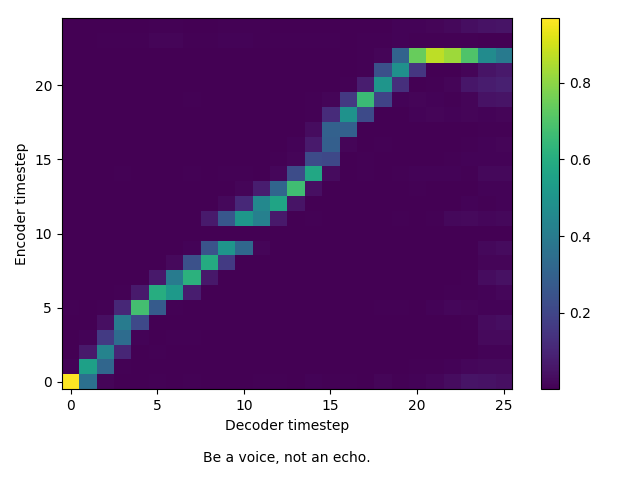

Alignment looks like this:

Yikes! Without a model showing alignment in training, “inference” would never work.

Issue 2: Data Malformation

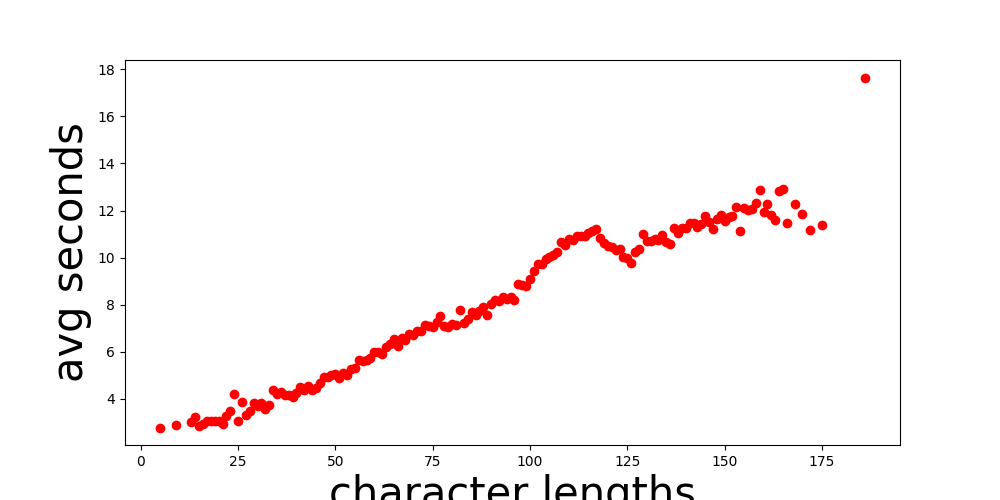

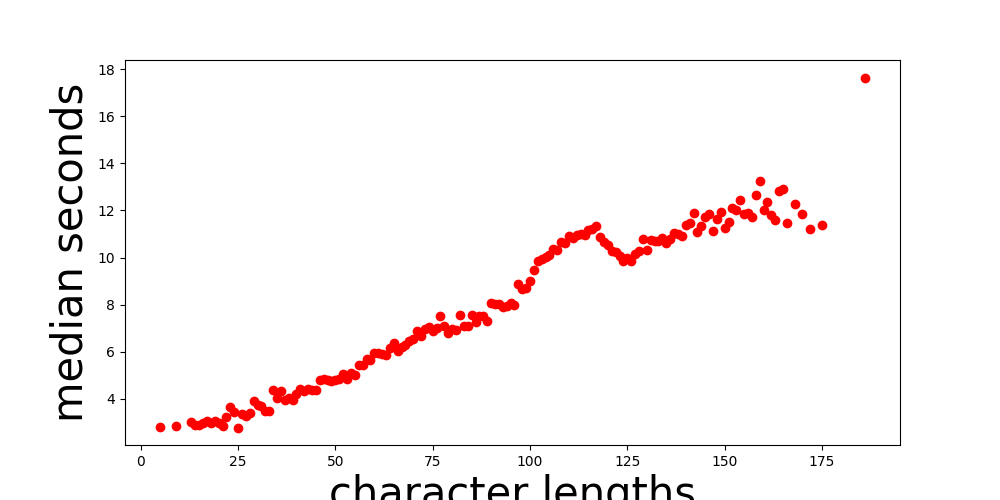

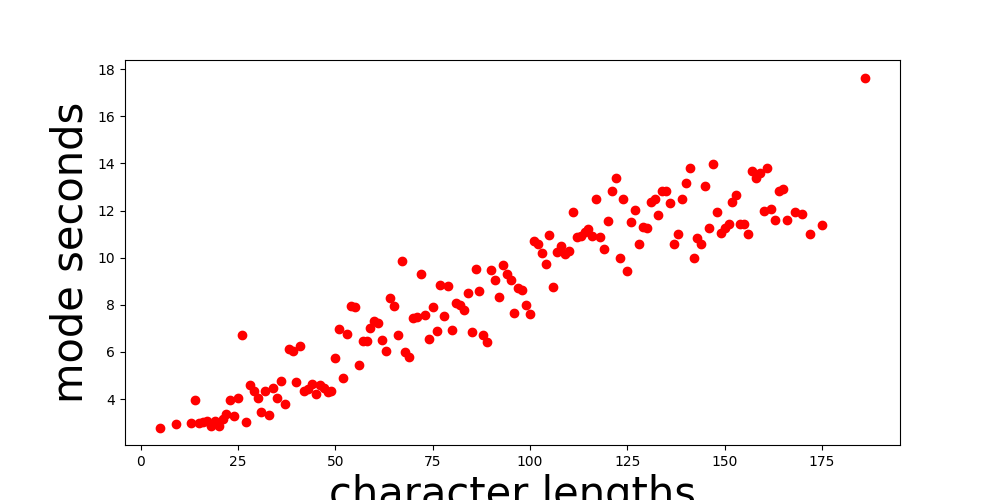

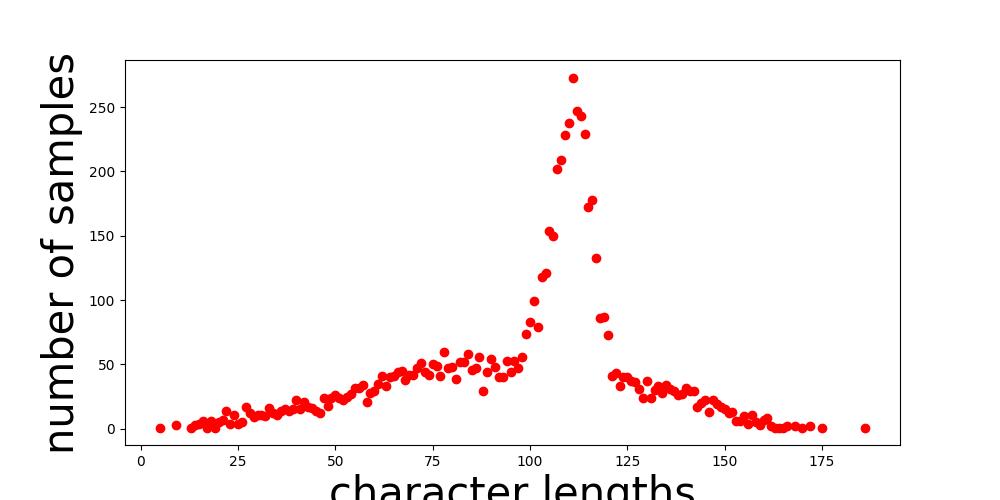

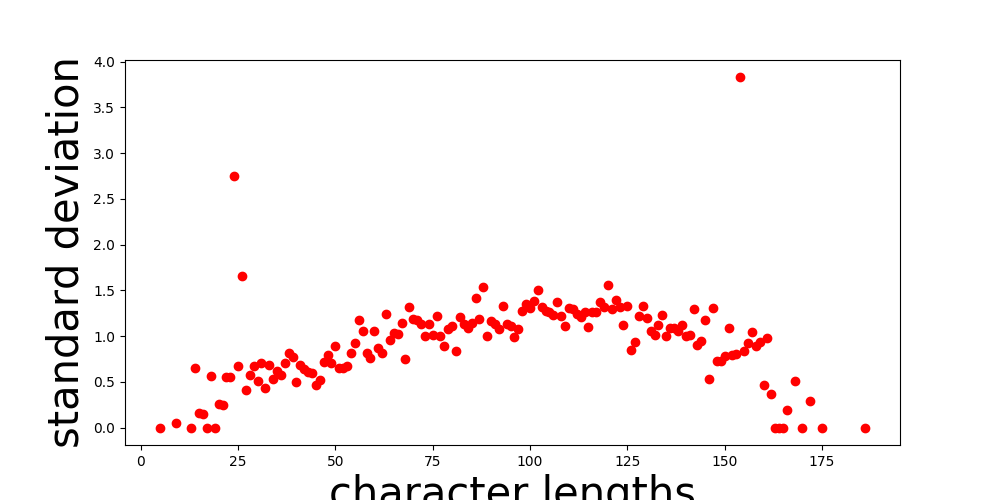

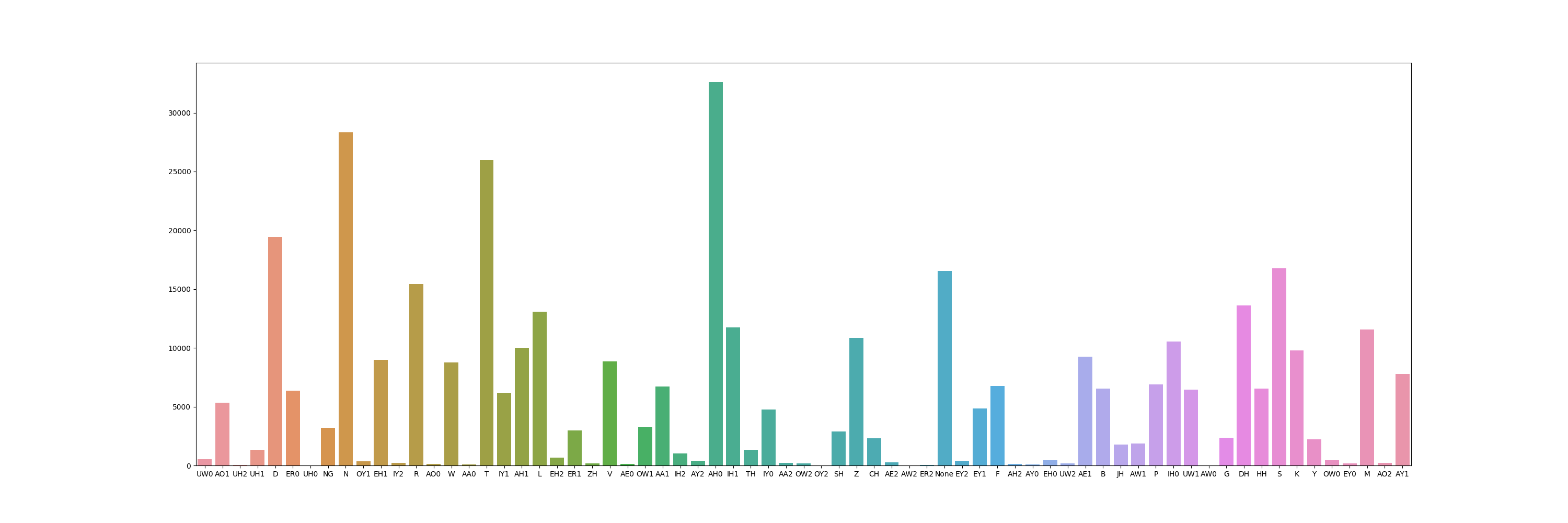

I also realised too late that Mimic2 provided me with a handy little tool for analysing my data before starting to train. Here are some examples demonstrating speech dataset analysis. It turned out that my data looked like the “bad” examples on this page, only worse. I tried some easy fixes, which chiefly included removing all files that were on the longer end, where the data was most chaotic. After that, I was left with analysis results that looked like this:

Character Length vs Average Seconds:

Character Length vs Median Seconds:

Character Length vs Mode Seconds:

Character Length vs Number of Samples:

Character Length vs Standard Deviation:

Phoneme Distribution (this, at least, does not represent a problematic result; it’s merely interesting):

I removed the obvious outliers in these graphs, but the data still wasn’t great. However, I was running out of time. As I discuss in my future plans, I will have to make a sweep of my entire speech dataset to clean it up further since my quality control process seems to have failed some non-trivial percentage of the time.

Finding Alignment

Due to time constraints, I needed to make the speech dataset work without further intervention. After reading many, many github issues, I realised that the issue with speech model alignment might be separate, at least in part, from the issues with data malformation. I read that Keith Ito’s initial implementation of tacotron was more forgiving than the mimic2 fork. Thus, I decided to change speech synthesis repos. I also made some changes to the hparams of the training script, to the bitrate of my wav files, and to the synthesis audio parser. These changes might have, in the end, made a bigger impact than the change of the synthesis repo. To be honest, I’m completely unsure what did the trick. I did send a tweet into the void with an offer to sell my soul in exchange for alignment, so it can’t be discounted that someone took me up on that. Whatever the cause, in the next round of training, my model quickly reached something like alignment.

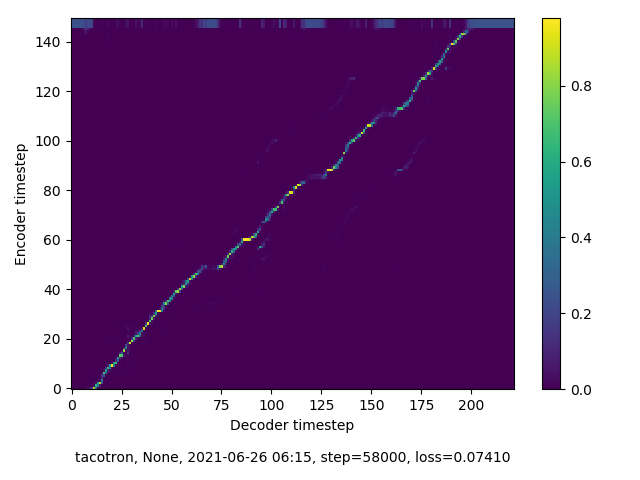

Here it is at 58,000 steps:

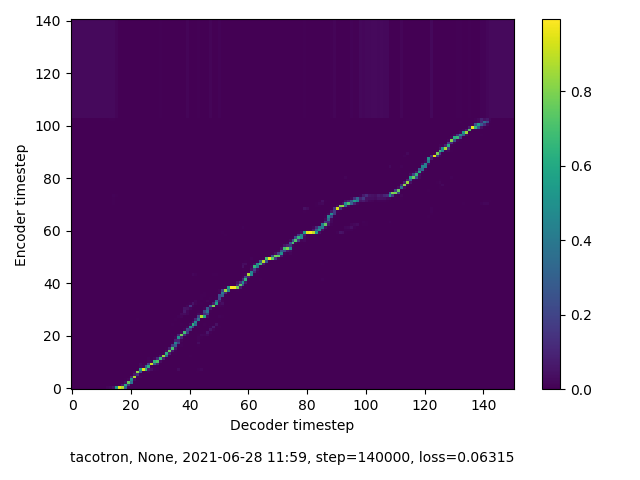

And at 140,000 steps, the furthest I ran training in the second round:

Audio and more visuals from training are available here.

Remaining Issues and Next Steps

Although inference was more successful with the model trained in this round, there were major problems with pacing, legibility, and timing. The changes that I made to the synthesis audio parser (per the github issue linked above) meant that synthesis doesn’t know where to “stop” – all output files are the same length, ending either with a long silence or an echo.

Were I to train a speech model again with this setup, I would perhaps try this slightly newer fork of Ito’s tacotron, which requires less training data and includes a “stop token” to solve the above problem file-length problem. However, as I discuss in my next steps section, I will likely first try the different training methods (one of which includes a tacotron implementation) maintained by Mozilla in their TTS repo. The tacotron implementations that I used for the prototype are aging rapidly, and requirements management is becoming a bit of a nightmare. Meanwhile, speech synthesis systems are rapidly improving, and it seems foolish to stick with training methods developed more than five years ago given the many newer innovations.

–

[^1] End-to-end voice synthesis describes a process for training a voice model in which no new information is input during the training process – the model is trained using only the data and parameters present at initiation; the system learns from itself recursively.